Download the article as a PDF or read below:

To facilitate efficient operations, employed provider networks should focus more on organizational structure and associated management infrastructure. Many employed provider networks still need to have a formal organizational chart.

Why is a formal organizational chart needed for employed provider networks?

The organizational chart visual represents the internal structure, exhibiting the different positions and departments and reporting structure of personnel.

An inadequately defined or nonexistent organizational structure is often the legacy of the employed network’s development. Most networks arose and grew serendipitously as physician practices approached hospitals and health systems for employment because of rising administrative burdens, EMR requirements, or financial sustainability concerns. As new practices were added and the network grew, often exponentially, the organizational structure expanded, but often in a piecemeal fashion, resulting in a patchwork quilt

design without much strategic consideration.

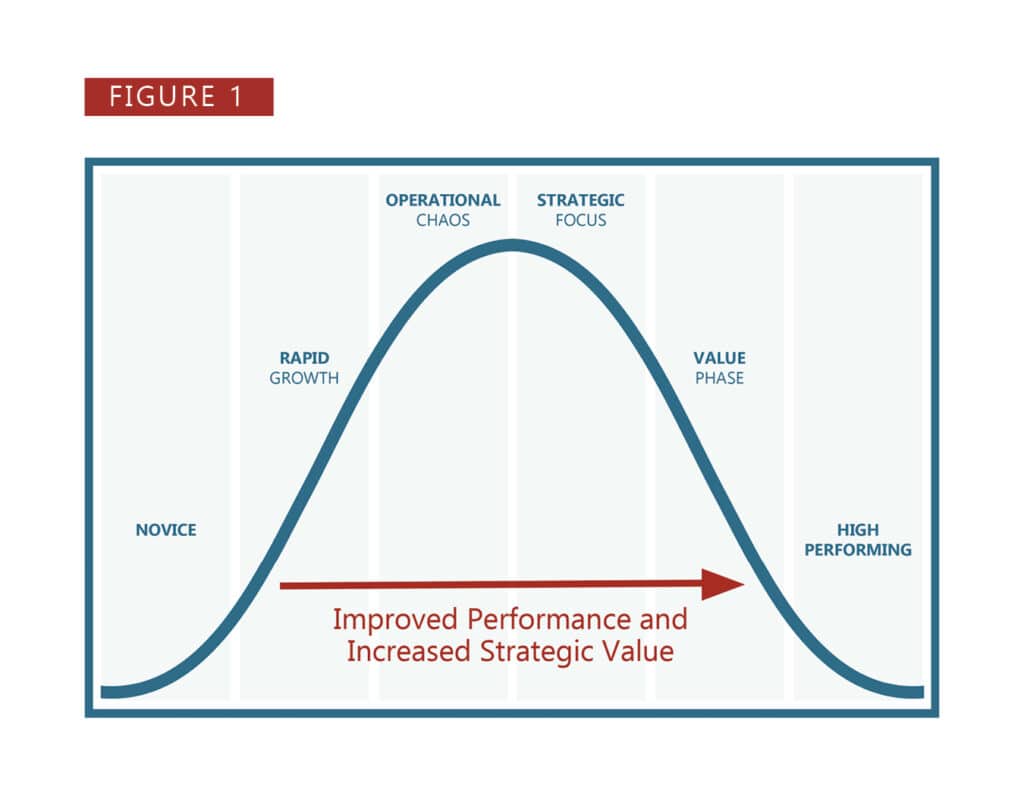

In addition, the management infrastructure often did not grow to accommodate the additional responsibilities, resulting in a mismatch emblematic of the Operational Chaos Phase of employed network growth and maturation, as seen in Figure 1.*

Why is employed provider network organizational structure so important?

The employed provider network’s organizational structure defines the reporting relationships and communication hierarchy that drives network operations and functions. Employed network members should know who to go to and what can be expected of those they report to. The “wire diagram” organizational chart defines the leadership and forms the backbone and skeleton upon which the management infrastructure, the management capabilities that support and optimize network operations, is built.

The titles noted in the structure must have clearly defined roles and responsibilities codified in specific position descriptions so that all organizational members understand the positional expectations and the individuals can be held accountable. Together, the organizational structure and the management infrastructure is the engine that drives the organization forward—both tactically and strategically.

While several types of organizational structures exist, the divisional approach seems to be the most common and practical for employed network function as it allows a clear reporting structure with flexibility to align similarly functioning or geographically located practices and permit a defined, reasonable span of control.

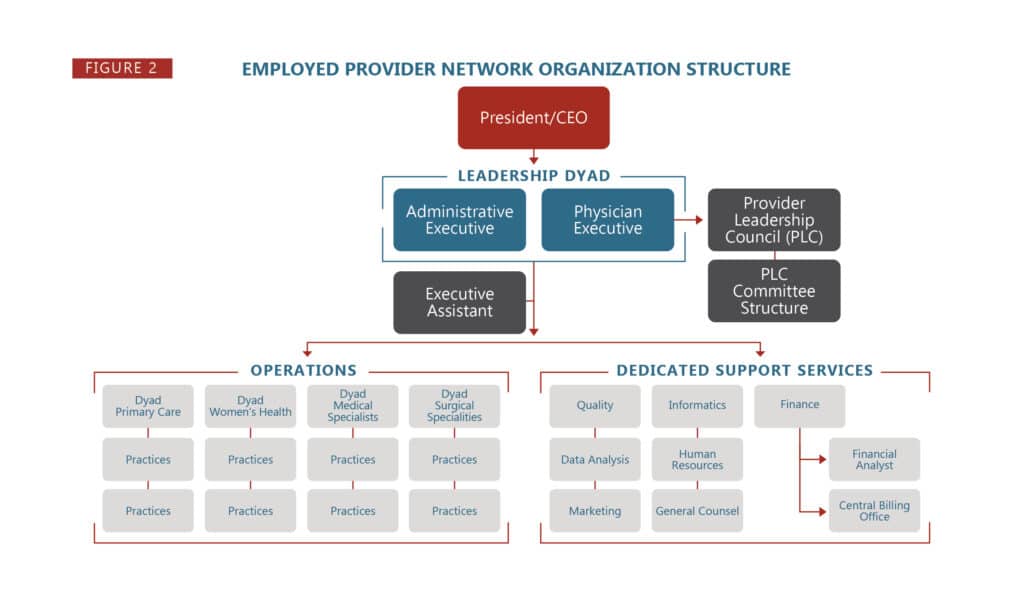

Most employed network organizational structures should consist of three interrelated functional elements, as noted in Figure 2:

■ Operations Management

■ Dedicated Support Services

■ Provider Leadership and Governance

Operations Management

The Operations Management area executes operational policy and procedure and runs the day-to-day operation of the practices. This functional area includes the operations directors and respective practice managers.

Adequately defined, staffed, and supported Operations Management allows providers and staff to feel well-supported and leads to more efficient and effective practice operations and outcomes—including enhanced provider and staff satisfaction, increased retention, and decreased burnout.

Within Operations Management, span of control and positional expertise are two essential keys for effective function. Appropriate span of control for most employed network organizational structures consists of 5-7 direct reports for each management individual in the hierarchy. The optimal span of control is important to allow adequate communication with and management of the resources under a reporting senior’s purview. The recommended span of control is associated with certain caveats—notably, all reporting personnel must possess the minimum knowledge, skills, and experience necessary to execute their individual duties and responsibilities effectively. This caveat has been loosely referred to having the right people in the right seats (positions).

However, the actual number of reasonable direct reports is influenced by the nature of organizational task(s) (complexity of operations, size of practices) and the distances between personnel and resources (remote locations). Even with its limitations, span of control defines the required numbers of management staff—assuming that each practice has designated onsite leadership for day-to-day practice management.

Dedicate Support Services

Without adequate Dedicated Support Services, the Operations Management portion of the organizational

structure will not achieve maximum effectiveness. As the name implies, the Dedicated Support Services

area provides support and augments specific expertise for network operations.

This functional area includes services such as coding and billing, information technology, finance, recruitment, human resources, marketing, and legal capabilities. Effectiveness in this area requires an adequate number of individuals with medical

practice expertise who are dedicated to supporting the employed provider network without being distracted by conflicting responsibilities and who are regularly involved in employed network operational and strategic discussions. Note the multiple caveats mentioned for these resources.

First, they must be “adequate in number.” Many employed networks do not commit sufficient resources to this element of the organizational chart, and as such, they routinely do not receive sufficient resources—to the detriment of both the employed network and the health system. National benchmarks exist that can help define the numbers of support FTEs based on numbers of providers supported.

Second, they must have “medical practice expertise”—which differs in many respects from hospital-based expertise, focus, and urgency. Third, they must be “dedicated” to the employed network—meaning that the employed network is their reason for being rather than an additional responsibility that it often overtaken by “larger” concerns within the health system.

Finally, these individuals should not just be resources that operations management can turn to when needed but should work side-by-side with the operations team to intimately understand circumstances and proactively provide timely input. These conditions hold true whether the resources are exclusively within the employed provider network’s leadership structure, reporting directly (solid line) to it, while also having an indirect (dotted line) reporting link to the health system’s leadership. Alternatively, they could operate as a “shared service,” directly reporting (solid line) to the health system’s hierarchy while maintaining an indirect (dotted line) reporting connection to the employed provider network’s leadership structure. The two arms of the employed network structure are intimately linked and require each to move hand-in-hand with the other for maximum mutual benefit.

Provider Leadership and Governance

Provider Leadership must be interwoven throughout the Organizational Structure. The importance of directly involving providers in the strategic planning and operational problem-solving and decision-making processes within the network has received heightened focus as the transition to value-based care has evolved. Success in the value-based care environment is proven to be based on the level of involvement of the physicians and other direct care providers in the foundational operations. Directly involving provider leadership also increases engagement, enhances alignment, promotes recruitment and retention success, and further mitigates burnout risk.

Provider leadership should be directly incorporated into the Operations Management portion of the organizational chart with the same, previously mentioned requirements for accurate position descriptions that clearly define the expectations, roles, and responsibilities. Provider leadership generally assumes two distinct forms—individual positional leadership (such as chief medical officers or medical directors) and group leadership (such as Provider Leadership Councils and associated committees). Both components permit direct involvement of providers in the network’s strategic planning, operational problem-solving, and decision-making processes.

Leadership positions are most effectively incorporated into the organizational chart in the form of dyad leadership/ management teams. Dyad leadership teams consist of administrative and provider pairs with joint operational management accountability through individual and shared responsibilities

delineated in their position descriptions. Establishing dyad teams involves more than just designating individuals for the roles.

The pairs’ interrelationships must be considered during the selection process and fully cultivated thereafter to ensure their individual strengths are utilized synergistically in their functional roles. Individuals placed in these roles may require specific training, coaching, and mentoring to be an effective team.

Further, while their roles need to be clearly understood by all staff, any staff member should be able to bring any issue or concern to either of the pair and the pair decide on the best manner to approach the issue or concern. Dyad leadership/management teams should be utilized throughout the network—from the executive level to the regional/divisional level to the individual practice level. Infusing physician leadership into the formal organizational structure in this manner unifies reporting relationships and optimizes operations.

Group leadership is often developed through Provider Leadership Councils (PLC), which report to and augment the executive level dyad leadership/management team. PLCs provide a mechanism to involve more employed network providers in the network’s problem-solving/decision-making/strategic planning processes and should be established through a formal Charter that defines its composition and functions. The composition of representative physicians, APPs, and network leadership should be inclusive enough to achieve broad input but small enough to effectively make decisions. Successful PLCs are supported by a committee structure that accomplishes the detailed work of the PLC and ultimately drives the PLC agenda. The committee structure allows more of the network providers to be involved in network operational initiatives through a multispecialty, multidisciplinary approach that promotes greater engagement and ownership of network actions and outcomes.

Taking the initiative to critically review the employed network’s organizational structure and redesigning it to best meet network needs should pay dividends associated with more efficient and effective clinical and business operations and enhanced provider and staff engagement and retention.

Learn more about nonproductivity incentives in provider compensation models.

Contact HSG Advisors’ expert in employed provider networks, Dr. Terrence R. McWilliams, MD, FAAFP at (502) 614-4292 or tmcwilliams@hsgadvisors.com