|

Download a PDF of this article to share with your team |

Burnout represents the culmination of situations in which the demands for time and productivity combine with insufficient time for recuperation to create a combination of physical and emotional exhaustion that leads to a continuing cascade and downward spiral.1

Symptoms of burnout reflect the results of ‘exhaustion’ and include altered diet and activity levels, cloudy judgement, forgetfulness, indecisiveness, anger, irritability, impatience, decreased self-esteem, decreased motivation and social withdrawal. These underpinnings result in outcomes such as an impaired ability to respond in a crisis, decreased empathy and cynicism, a diminished sense of accomplishment, and decreased satisfaction with life in general and work in particular.

EFFECTS OF PHYSICIAN BURNOUT

Physician burnout can lead to grave personal and profession consequences for the individual.

- Personal interpersonal relationships suffer, potentially leading to loss of friends or marital separation or divorce. The individual may self-medicate, leading to substance use disorders. The symptom complex can even progress to major depression and an increased risk for (or successful) suicide.

- Professional interpersonal relationships with patients and staff suffer. Productivity declines. Medical error rates, adverse patient outcomes, and malpractice litigation risks increase. The individual’s reputation and professional future are jeopardized.

Physician burnout also adversely affects many aspects of the organization including –

- Provider availability on a daily basis and provider attrition on a long-term basis. Physician turnover/loss rates are higher for physicians with burnout.6

- Patient experience suffers – with risk of patient loss.

- Staff morale declines – with risk of impaired retention and increased turnover.

- Operational efficiency decreases.

- Quality of care and patient safety decline as medical errors increase.

- Malpractice litigation risk increases.

- Cost of care surges through physician indecisiveness, increased referral and testing rates, and adverse malpractice judgments.

PHYSICIAN BURNOUT PREVENTION

Preventing physician burnout, or identifying and addressing burnout in its earliest stages, is mutually beneficial to the affected physicians, the patients they serve, the staff with whom they work, and the organizations which they support. As such, burnout lends itself to primary, secondary, and tertiary preventive efforts.7

PRIMARY PREVENTION

Primary prevention initiates actions to help avoid developing certain health problems or unbeneficial conditions. The actions are taken before the problem(s) occur with the goal of preventing a condition from occurring and include preventing exposure to causal hazards, altering unhealthy or unsafe behaviors, and increasing resistance should an unsafe exposure occur.

Primary prevention of physician burnout involves heightening personal resilience and developing organizational programs that create a less stressful work environment.

While primary prevention efforts may not be 100% effective in absolutely preventing the targeted condition in all situations, these interventions decrease both incidence (new cases) and prevalence (persisting current cases) rates.

SECONDARY PREVENTION

Secondary prevention efforts attempt to interrupt an asymptomatic condition before it becomes symptomatic – or at least catch a condition in its early stages, when few signs and symptoms are present. The goal is to intervene early to halt or slow the progression of the condition.

Applied to burnout, the goal is to detect early symptoms of burnout (or symptoms that indicate an increased risk of burnout) and intervene before negatively impacting the individual and those around him/her. Regular screenings for evidence of burnout would qualify as a secondary prevention effort.

TERTIARY PREVENTION

Tertiary prevention attempts to minimize the adverse consequences of an established, ongoing condition. These interventions improve the ability to function with the condition and improve quality of life. In this instance, interventions try to prevent the consequences of a diagnosed condition from being any worse than it currently is and to minimize adverse effects from it.

Applied to burnout, the individual meets diagnostic criteria for burnout and intervention is intended to improve circumstances and avoid further deterioration of relationships, adverse professional consequences, substance use disorder, severe depression, or suicide.

BUILDING A MITIGATION PROGRAM

Although burnout has many contributing factors, organizations can implement burnout mitigation programs – often referred to as physician wellness programs – to make a difference in burnout prevalence and severity.1, 8 Program elements are based on minimizing the risk of developing burnout (primary prevention) and detecting any evidence of burnout to actively intervene and minimize consequences (secondary and tertiary prevention depending on degree).

Burnout Mitigation Programs include the following elements:

Physician Leadership

Formally imbedded in the organizational structure, directly involved in organizational problem-solving and decision-making processes, and a key component of transparent, open, bidirectional communication between Administration and physicians.

Workplace Wellness Programs

Provides resources and opportunities for personal wellness programs that promote resiliency.9, 10, 11

Just Culture Development

Sets the tone for open reporting without fear of retribution and establishes a non-punitive foundation for systemic improvement.12

Provider Impairment Policy

Creation, implementation, and promotion of a Provider Impairment Policy establishes organizational processes and sets cultural expectations related to impairment.

BUILDING A MITIGATION PROGRAM

Screening, Monitoring, and Reporting

Developing an ongoing monitoring and reporting program for the presence of burnout characteristics actively conveys interest in and concern for provider well-being. Utilizing validated survey tools (such as the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI), the Mini Z,9 or single items screens)13, 14 standardizes the approach to identifying and tracking burnout and reporting results to physicians and staff establishes an open culture, launches dialogue, and permits targeted improvement efforts.8, 15

Chief Wellness Officer

Adding this position to senior leadership elevates the stature of and awareness for physician wellness and dedicates sufficient attention and resources to it.5, 9

Education

Ensures that all staff are aware of burnout risk, recognition, and intervention.

Direct EHR Support

EHRs are major drivers of physician stress and practice dissatisfaction,5, 16, 17 which can be reduced through organizational awareness of EHR impact and associated decision-making. Support components include platform selection input, elbow-to-elbow support, recurrent process automation, ongoing training opportunities, adequate hardware and connectivity, and appropriate adjuncts such as speech recognition software, clinical informatics workgroups, and utilizing scribes.

Culture

Program elements ultimately drive an organizational culture that embraces sincere communication and collaboration, values work-life balance, meets regularly to interact and socialize as a group, recruits and hires for cultural fit, and continually promotes physician and staff well-being.

Transitioning to a team-based care delivery model designed to share the care delivery “burden” among all staff and utilize all staff members at the top of their license and capabilities has been shown to mitigate physician burnout risk1,8,18,19,20 but requires significant paradigm shifts to accomplish. Physicians must relinquish some traditional responsibilities18 and support staff must accept changes in their roles and be adequately trained to assume them.21 Success implementation of the model creates additional organization benefits related to streamlined clinical operations, greater professional fulfillment, more comprehensive patient care, and enhanced patient satisfaction and engagement.

Physician burnout and its adverse effects on individuals and systems can be effectively addressed through concerted efforts and investments related to primary, secondary, and tertiary preventive efforts at the organizational level. The benefits of an active program predictably far exceed the positive impact on burnout alone. If you would like to begin a discussion around building a burnout mitigation program for your health system, contact Dr. Terry McWilliams at (502) 614-4292.

CITED REFERENCES

- Goodman M., and Berlinerblau M., Discussion: Treating Burnout by Addressing Its Causes. American Association for Physician Leadership News, January 5, 2018. https://www.physicianleaders.org/news/discussion-treating-burnout-by-addressing-its-causes

- Porter S., How Small NYC Primary Care Practices Avoid Burnout Blues. American Academy of Family Physicians Primary Care Research, July 31, 2018. https://www.aafp.org/news/focus-on-physician-well-being/20180731burnoutsmallpract.html

- Bodenheimer T., Sinsky C., From Triple to Quadruple Aim: Care of the Patient Requires Care of the Provider. Annals of Family Medicine, Vol. 12, No. 6, November/December 2014.

- Medscape National Physician Burnout, Depression & Suicide Report 2019. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2019-lifestyle-burnout-depression-6011056

- Jha A., et al, A Crisis in health Care: A Call to Action on Physician Burnout. Massachusetts Medical Society, January 17, 2019

- Willard-Grace R., et al, Burnout and Health Care Workforce Turnover. The Annuals of Family Medicine, Vol. 17, No. 1 (36-41), January/February 2019.

- Institute for Work & Health.

- Klevos G., Ezuddin N., In Search of the Most Effective Interventions for Physician Burnout. American Association for Physician Leadership News, May 15, 2018. https://www.physicianleaders.org/news/discussion-burning-brightly-burning-out

- Van Dyke M., Battling Clinician Burnout: Fighting the Epidemic from Within. Healthcare Executive, JAN/FEB 2019.

- Harvard Business Review, Three Ways to Prevent Your Team from Burning Out. Harvard Business School Publishing Corp. distributed by The New York Times Syndicate, February 14, 2019. https://www.physicianleaders.org/news/three-ways-prevent-your-team-burning-out

- Olden C., Burnout Part 2: Adopting a Systems Approach to Prevention. American Academy of Family Physicians Leader Voice Blog, February 19, 2018.

- Boysen P., Just Culture: A Foundation for Balanced Accountability and Patient Safety. The Ochsner Journal, 2013 Fall; 13(3): 400–406. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3776518/

- West C., Dyrbye L., Sloan J., Shanafelt T. Single item measures of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization are useful for assessing burnout in medical professionals. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(12):1318–21.

- Dolan E, et al, Using a Single Item to Measure Burnout in Primary Care Staff: A Psychometric Evaluation. J Gen Internal Med. 2015;30(5):582-7.

- Shanafelt, T., Noseworthy J., Executive Leadership and Physician Well-Being: Nine Organizational Strategies to Promote Engagement and Reduce Burnout. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, January 2017:92(1):129-146.

- Family Physician Burnout, Well-Being, and Professional Satisfaction (Position Paper). American Academy of Family Physicians, June 1, 2018.

- Garner R., et al, Physician stress and burnout: the impact of health information technology. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, Volume 26, Issue 2, 1 February 2019, Pages 106–114. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocy145

- Kim L., et al, Primary Care Tasks Associated with Provider Burnout: Findings from a Veterans Health Administration Survey. Journal of General Internal Medicine, January 2018, Volume 33, Issue 1, pp 50-56. https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007%2Fs11606-017-4188-6.pdf

- Kreimer S., Team-Based Approach Puts Dent in Physicians’ EHR ‘Pajama Time’. October 3, 2017. https://www.physicianleaders.org/news/team-based-approach-puts-dent-in-physicians-ehr-pajama-time

- Reuben D., Sinsky C., From Transactional Tasks to Personalized Care: New Vision of Physicians’ Roles. Annals of Family Medicine, Vol. 16, NO. 2, March/April 2018. http://www.annfammed.org/content/16/2/168.full

- Jerzak J., Using Empowered CMAs and Nursing Staff to Improve Team-based Care. Family Practice Management, 2019 Jan-Feb;26(1):17-22.

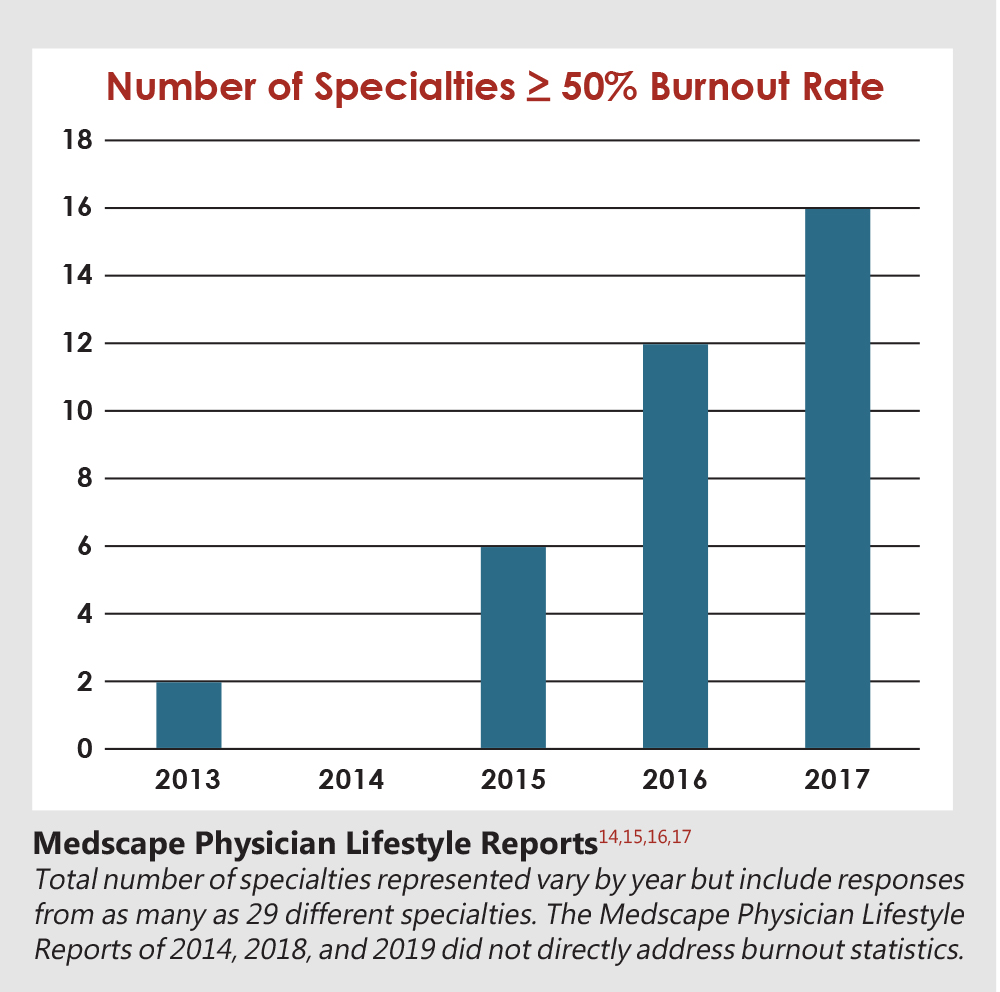

- Medscape Physician Lifestyle Report 2013. https://www.medscape.com/features/slideshow/lifestyle/2013/public

- Medscape Physician Lifestyle Report 2015. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/lifestyle-2015-overview-6006535

- Medscape Physician Lifestyle Report 2016. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/lifestyle-2016-overview-6007335

- Medscape Physician Lifestyle Report 2017. https://www.medscape.com/features/slideshow/lifestyle/2017/overview#page=1